Pirrong Debunks the Keynesian

Debunking

By Robert Higgs

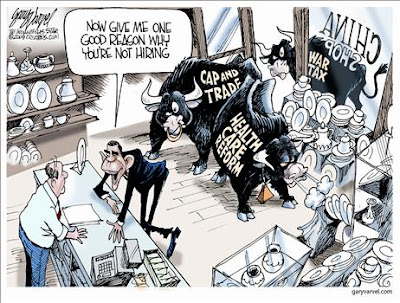

As the idea of regime uncertainty

has gained ground in recent years as a partial explanation of the economy’s

failure to recover quickly and fully, economists and others invested in

Keynesian thinking have begun to strike back. One such Keynesian debunking of

regime uncertainty was offered recently by Gary Burtless and seemingly endorsed

by Mark Thoma. Now, Craig Pirrong, an economist at the University of Houston,

has debunked Burtless’s arguments.

As the idea of regime uncertainty

has gained ground in recent years as a partial explanation of the economy’s

failure to recover quickly and fully, economists and others invested in

Keynesian thinking have begun to strike back. One such Keynesian debunking of

regime uncertainty was offered recently by Gary Burtless and seemingly endorsed

by Mark Thoma. Now, Craig Pirrong, an economist at the University of Houston,

has debunked Burtless’s arguments.

Pirrong uses options pricing theory

to show why the Keynesians are missing the point of the regime uncertainty

concept and why, even on their own terms, their arguments for disregarding

regime uncertainty and simply pumping up aggregate demand are wrong.

To adapt a familiar saying: first they ignore you, then they ridicule

you, then they embrace the idea and claim that they had it first. We are now

passing through Stage II.

Although I am pleased that the

concept of regime uncertainty has come to be recognized in some quarters as an

important part of our understanding the economy’s operation, I continue to be

disconcerted that many of those who speak of it, including some of those who

speak favorably of it, fail to understand its full scope. As I understand

regime uncertainty, it has to do with widespread inability to form confident

expectations about future private property rights in all of their dimensions.

Private property rights specify the property owner’s rights to decide how

property will be used, to accrue income from its uses, and to transfer these

rights to others in various voluntary arrangements. Because the content of

private property rights is complex, threats to such rights can arise from many

different sources, including actions by legislators, administrators,

prosecutors, judges, juries, and others (e.g., sit-down strikers, mobs).

Because of the great variety of ways

in which government officials can threaten private property rights, the

security of such rights turns not only on law “on the books,” but also to an

important degree on the character of the government officials who administer

and enforce the law. An important reason why regime uncertainty arose in the latter

half of the 1930s, for example, had to do with the character of the advisers

who had the greatest access to President Franklin Roosevelt at that time—people

such as Tom Corcoran, Ben Cohen, William O. Douglas, Felix Frankfurter, and

others of their ilk. These people were known to hate businessmen and the

private enterprise system; they believed in strict, pervasive regulation of the

market system by—who would have guessed?—people such as themselves. So, as bad

as the National Labor Relations Board was on paper, it was immensely worse (for

employers) in practice. And so forth, across the full range of new regulatory

powers created by New Deal legislation. In a similar way, the apparatchiki who

run the federal regulatory leviathan today can only inspire apprehension on the

part of investors and business executives. President Obama’s cadre of crony

capitalists, which he drags out to show that “business is being fully

considered,” in no way diminishes these worries.

Thus, regime uncertainty is a

multifaceted and somewhat nuanced concept. Many economists don’t like it

because it cannot be measured and compiled along with other standard macro

variables in a convenient data base. But, as I have tried to show for fifteen years,

various forms of empirical evidence can be and have been brought to bear to

show that regime uncertainty is not simply a figment of the analyst’s

imagination or an all-purpose club with which the Chamber of Commerce whacks

the government’s every move to increase taxes or augment regulations. Anyone

who actually manages a business or makes serious investment can readily

understand the idea. Keynesian economists, who generally do not manage

businesses or make serious investments, view the idea as merely something their

ideological opponents toss out to obstruct the application of their “science”

in policy making. It is good to have analysts such as Craig Pirrong showing

that the Keynesian rejection of regime uncertainty has no firm foundation.

No comments:

Post a Comment