by Peter C. Earle

Can a community without a central government avoid

descending into chaos and rampant criminality? Can its economy grow and thrive

without the intervening regulatory hand of the state? Can its disputes be

settled without a monopoly on legal judgments? If the strange and little-known

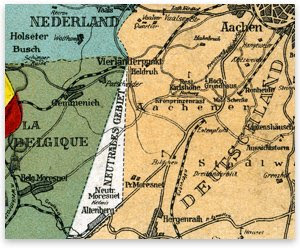

case of the condominum of Moresnet — a

wedge of disputed territory in northwestern Europe, and arguably Europe's counterpart

to America's so-called Wild West — acts as our guide, we must conclude that

statelessness is not only possible but beneficial to progress, carrying

profound advantages over coercive bureaucracies.

The remarkable experiment that was Moresenet was an

indirect consequence of the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), which, like all wars,

empowered the governments of participating states at the expense of their

populations: nationalism grew more fervent; many nations suspended specie

payments indefinitely; and a new crop of destitute amputees appeared in streets

all across Europe.

In the Congress of Vienna, which concluded the war,

borders were redrawn according to the "balance-of-power" theory: no

state should be in a position to dominate others militarily. There were some

disagreements, one in particular between Prussia and the Netherlands regarding

the miniscule, mineral-rich map spot known as the "old mountain" —

Altenberg in German, Vieille Montagne in French — which held a large zinc mine

that profitably extricated tons of ore from the ground. With a major war

recently concluded, and the next nearest zinc source of any significance in

England, it behooved the two powers to jointly control the operation.

They settled on an accommodation; the mountain mine would

be a region of shared sovereignty. So from its inception in 1816, the zone

would fall under the aegis of several states: Prussia and the Netherlands

initially, and Belgium taking the place of the Netherlands after gaining its

independence in 1830. Designated "Neutral Moresnet," the small land

occupied a triangular spot between these three states, its area largely covered

by the quarry, some company buildings, a bank, schools, several stores, a

hospital, and the roughly 50 cottages housing 256 miners and support personnel.[1]

The first factor is that, although nominally monitored

by several nations, by virtue of its small size, Moresnet was loosely

supervised at best. Not only was it so small that a crumb would blot out its

existence on most maps; neither was there much reason for its overseers to

direct attention to it: it sat quietly, reliably excavating 8,500 tons of zinc

each year. Occasionally a patrolling Prussian, Dutch, or Belgian soldier would

wander close to the border — as a demilitarized zone, Moresnet territory was

explicitly off limits for military forces — but for the most part the mining

community was left alone.

And it wasn't just administrators who lost track of

the of the anomalous territory; it was secluded enough that one traveler

recalled inquiring at [a nearby] hotel, at some neighboring shops, and at both

of the railway stations … [but still couldn't be told] how to reach Neutral

Moresnet; they had no idea at all, or guessed at random at various impossible

stations.[3]

Within the triangle, there was a minimal government in

the form of a burgomaster, assisted by a "Committee of Ten." Despite

its somewhat ominous name, the committee "wield[ed] no real power"

and the burgomaster was "far from being a … despot."[4]

Moresnet also employed a police force of one, referred

to with local good humor — and perhaps mocking nearby Prussia with its General

Staff and large social class of military officers — as Moresnet's

"Secretary of War."[5] The lone police officer was usually "to be

seen in full uniform enjoying a game of chess or billiards with the burgomaster

at the beer garden on the shores of the lake."[6]

Through the rest of the 19th century, Moresnet's course

ran distinct from that of surrounding European states. In 1848, for example,

violent revolutions broke out in Italy, France, Germany, Denmark, Hungary,

Switzerland, Poland, Ireland, Wallachia, the Ukraine, and throughout the

Habsburg Empire. For Moresnettians, life in 1848 proceeded unperturbed, and the

year was noteworthy only for the first minting of sovereign coins, which local

merchants accepted for use alongside other currencies.[7]

Despite its isolation, word slowly spread that within

Moresnet — if one could find it — "imports from surrounding countries were

toll free, the taxes were very low, prices were lower and wages higher than in

[other European] countries."[8]

Over the following decades the population of the tiny

region grew correspondingly: by 1850, the population had doubled, and in

addition to the zinc mine, new businesses and even some small farms began to

spring up.

Alongside the negligible tax burden, a unique legal

climate favored the expansion of economic activity within the tiny district. On

inception, the Congress of Vienna, which created Neutral Moresnet, held that

its laws would be construed in accordance with the Code Napoleon, known for its stress on clearly

written and accessible law, [which] was a major step in replacing the previous

patchwork of feudal laws.… Laws could be applied only if they had been duly

promulgated, and only if they had been published officially (including

provisions for publishing delays, given the means of communication available at

the time); thus no secret laws were authorized. It [also] prohibited ex post

factor laws.[9]

And most importantly of all, the code placed a primary

importance on "property rights … [which] were made absolute,"

naturally generating a favorable climate for commercial enterprise.[10] One periodical noted that a "thief tried …

[nearby] gets … a few months, while the Code Napoleon specifies

five years."[11]

This contrasted sharply with the Allgemeines Landrecht legal system of

neighboring Prussia, which "used an incredibly casuistic and imprecise

language, making it hard to properly understand and use in practice," but

which for some legal purposes may have held advantages over the Code Napoleon. [12]Alternately,

disputes could be directed to the burgomaster's "petty tribunal" for

quick decisions on smaller issues and disputes.[13] His head-quarters were … "under his

hat." He went about town and held court wherever he happened to be when

his service as justice was required, which, happily, was not often. When

complaint was made to him, he would listen patiently and attentively … [then]

whistle some favorite air, and thus take time to resolve the matter in his

mind.… His judgments were always intelligible and fair, insomuch that they were

never excepted to or appealed from during all his term of thirty-five years.[14]

Moresnet inhabitants, therefore, had access to several

different systems for resolution of disputes — a rudimentary market for justice

— and were therefore empowered to take their issues to the venue they felt

afforded the best chances of satisfactory resolution.

Further, residents of Neutral Moresnet were not

required to fulfill the compulsory military requirements of their nations of

origin.[15] This no doubt motivated many of the new

arrivals, in particular those from Prussia, which fought half a dozen wars

during the 19th century.[16]

The population of the hamlet quadrupled between 1850

and 1860, topping 2,000 residents. One newcomer was particularly significant.

Dr. Wilhelm Molly arrived in 1863 to become the general practitioner of the

mining company, and soon won celebrity by thwarting a local cholera epidemic in

Moresnet. Like many physicians of his era, Dr. Molly had numerous interests,

some of which would play a role in Moresnet's development over the next

half-century.[17]

From the beginning of the designation of Neutral

Moresnet, it was known that the Vieille Montagne zinc mine could not, and would

not, produce indefinitely. In 1885, the zinc mine finally wound down and ceased

operation, but this wasn't especially worrisome economically: numerous

businesses were now flourishing, including "60–70 bars and cafes [along]

the main street," a number of breweries, small farms, and at least one

dairy operation.[18] Taxes hadn't changed since the designation of

the neutral zone in 1816, and visitors noted that Moresnet was "without

the beggars who are [a] sadly familiar sight" across the rest of Europe.[19]

To Dr. Molly, the closing of the zinc mine hardly

presented reason for the culmination of Neutral Moresnet as a community, much

less its end. On the contrary, he became the foremost advocate of pursuing a

path of complete independence and severing the few ties that Moresnet had with

Prussia and Belgium. Within a year after the zinc mine closed down, he

spearheaded the founding of a local, private postal service — but it was

quickly shut down by Prussian and Belgian authorities.

Undeterred, he explored numerous other initiatives. In

1903, a group of entrepreneurs proposed developing a casino there to rival

those in Monte Carlo, offering to build electric trolleys to nearby towns and

"share the profit with every citizen."[20] In fact, a small casino opened briefly, but like

the postal service was short-lived; on hearing of it, the king of Belgium

threatened Moresnet's always-tenuous independence.

But Belgium proved the least of Moresnet's worries. In

1900 the Prussian state — now itself consolidated into the greater German

Empire — began to undertake "aggressive" tactics towards pressuring

the residents of the zone to consent to absorption.[21] None too subtle and true to its martial

heritage, Prussian efforts included "outright sabotage," such as

cutting off Moresnet's electricity and telephone connections at times.[22] When citizens attempted to run new electrical

and telephone lines, Prussia attempted to thwart them, as well as

"prevent[ing] the appointment of new … officials" known to support

Moresnettian independence.[23]

But "these people, small though their territory,

w[ould] not be cabined, cribbed, confined."[24] In fact, despite being harassed by a state

thousands of times larger and armed to the teeth, by 1907 the population of the

hamlet had increased to almost 3,800, only 460 of whom were descendents of the

original Moresnettians.[25] The rest came from varied and far-flung

locations: not only Germans, Belgians and Dutch, but also former residents of

Italy, Switzerland, and Russia — and eventually two Americans and even one

Chinese resident. A large cathedral had come to occupy the center of the

community, which had expanded to over 800 homes.[26] Even though Belgian Aix-la-Chapelle was nearby

and offered a more cosmopolitan experience, in general, the Moresnettians chose

"not [to] leave the Triangle, but variedly find the spice of life within

its slender borders."[27]

Dr. Molly — now living in the "thoroughly

autonomous" Neutral Moresnet for half a century — began to view the

independence and prosperity of Moresnet as a place compatible with the Weltanschauung of another of his intellectual

pursuits: the universal language and culture of Esperanto.[28] While a detailed discussion of Esperanto is

beyond the scope of this writing, the synthetic language was founded in 1887 by

L.L. Zamenhof to eliminate the "hate and prejudice" that he theorized

arose between ethnic groups owing to language differences and often leading to

war; and it should come as little surprise that Esperanto's founder

additionally expressed his profound [conviction] that every nationalism offers

humanity only the greatest unhappiness.… It is true that the nationalism of

oppressed peoples — as a natural self-defensive reaction — is much more

excusable than the nationalism of peoples who oppress; but, if the nationalism

of the strong is ignoble, the nationalism of the weak is imprudent; both give

birth to and support each other.[29]

Embracing this thinly veiled antistate philosophy and

having corresponded for years with prominent Esperantists around the world, in

1906, Dr. Molly met with several colleagues to discuss designating Neutral

Moresnet as a self-determining global haven for Esperantists; a territory that

would "embrace aims and ideals affecting the brotherhood of man …

civilized life … emancipating ourselves from all that is absurd and unworthy in

convention, all that the ignorant centuries have imposed upon us."[30]Core to that initiative, he proposed that the name of

the enclave be changed to Amikejo — Esperanto for "place of

friendship" — not only espousing their explicitly peaceful nature, but

undoubtedly a propagandist thumb in the eye of ever-marauding Prussia.[31]

Two years later, in 1908, a large celebration was held

commemorating the launch of the renamed Amikejo, complete with festivities and

the airing of a new national anthem. [32] Unsurprisingly,

the occasion went unnoted (and Amikejo unrecognized) by nearby states, although

numerous newspapers reported the event.

By 1914, Amikejo's population topped 4,600 people,

peacefully cohabitating in an economically prosperous political limbo

characterized by an "absence of definite rule."[33] Signs and notifications were printed in German,

French, and Esperanto, and residents had developed one of the "queerest

and most unintelligible dialects in the world."[34] Indeed, an American — an American of the turn of

the century, no less — described the establishment as having "a sort

of al fresco freedom of life, an untrammelledness

which comes naturally from long-continued absence of centralized

restraint."[35]

Indeed; for a century, residents and settlers in the

diminutive wedge of land had found governments — internally and foreign —

superfluous to and iniquitous toward the attainment of individual liberty. In one

sense the Moresnet/Amikejo experiment might be viewed as Europe's analog to

the American West, covering a

greater length of time but on a much smaller scale. Summarizing, one reporter

described it as one of the smallest and strangest territories in the world … an

encircling ridge of high mountains veritably buries it from neighboring

civilization and culture and leaves it in a little world of its own.… [And] for

nearly a century, the inhabitants have never experienced the feeling of being

under the rule of an emperor, king or president. They are independent, governed

by no one, at liberty to do as they please.[36]

Despite a vibrant, small-scale economy, the existence

of the district remained enormously fragile in the tempestuous political

environment of early 20th-century Continental Europe. Amikejans perennially

worried over the "impermanency of their pleasing status," and this

concern was realized in 1914 when war broke out between France and Germany. [38] Although

Amikejo escaped destruction as invading German forces bypassed it — it was,

fortuitously, "an oasis in a desert of destruction" — the War proved

a ready excuse, confirming the suspicion that "Prussia … always had the

intention to appropriate the territory" when Germany statutorily annexed

the district in 1915.[39]

Two inconceivably bloody years later, with the end of

the war in sight, only the Contemporary Review,

a British journal of politics and social reform, considered the plight of

Amikejo née Moresnet:

The fate of Moresnet has been forgotten in this

immense catastrophe. We must bear it in mind. After the victory the

plenipotentiaries who draw up the conditions of peace must not neglect this

poor little piece of independence which has been victimized.[40]

The cost of the Great War was unimaginably staggering,

dwarfing those of previous conflicts in virtually every category: 37 million

casualties, the influenza pandemic, widespread hunger, civil dislocation,

economic wreckage, and more. But another, seldom-considered consequence of the

war — of all wars — was, and is, the uncountable heaps of unfulfilled promises

and discarded goals left in the wake of the conflagration. And with article 32

of the Treaty of Versailles — "Germany recognizes the full sovereignty of

Belgium over the whole of the contested territory of Moresnet"[41] — these were joined by yet another: Dr. Molly's

vision.

Notes

[2] Robert Shackleton, Unvisited Places of Old Europe (Philadelphia: The

Penn Publishing Company, 1913), p.157.

[11] A Manual of Belgium and the Adjoining

Territories. Naval Intelligence Division. (Great Britain: H. M. Stationary

Office, 1918) p. 246.

[14] William S. Walsh, A Handy Book of Curious Information (Philadelphia:

J. B. Lippincott Company, 1913) p. 558-559.

[15] Both Belgium (1847) and Prussia (1875)

ultimately rescinded their exemption of emigrants in the Moresnet zone from

conscription military service.

[17] The Moresnet.nl website notes that Wilhelm Molly

was awarded the Geheimrat title by Prussia,

which translates to "special [medical] counselor." This author finds

amusement in noting that the term may have incurred ironic gravity over time as

it was also used by German Kaisers to refer to academics that irritated them,

as Molly's heroic efforts in Moresnet/Amikejo undoubtedly did.

[28] Links between anarchism/libertarianism and

Esperanto are copious, if perplexingly underinvestigated. While a portion of

Esperanto's usage has always been co-opted by leftist and Utopian groups, its

founding principle was anti-state to the extent that it was created to skirt

nationalism and provide possibilities for more seamless, peaceful interaction:

facilitating trade and avoiding violent conflict. The great writer and

linguistics genius J. R. R. Tolkien, who occasionally espoused anti-state views

("My political opinions lean more and more to anarchy. The most improper

job of any man, even saints, is bossing other men.") wrote, "My

advice to all who have the time or inclination to concern themselves with the

international language movement would be: 'Back Esperanto loyally.' See "La Filozofio de Libereco" ("The

Philosophy of Liberty"), ISIL.org.

[29] N. Z. Maimon, "La Cionista Periodo en la

Vivo de Zamenhof," Nica Literatura Revuo 3/5:

p. 165–177.

[37] Louis Viereck, "Moresnet — The Smallest

State on Earth," The Fatherland Vol

III, No. 2 (1915): 33.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment