If the coast of California is

“postmodern,” as its residents like to say, we in the state’s interior are now

premodern. Out here in the San Joaquin Valley, civilization has zoomed into

reverse, a process that I witness regularly on my farm in Selma, near Fresno.

Last summer, for example, intruders ripped the copper conduits out of two of my

agriculture pumps. Later, thieves looted the shed. I know no farmer in a

five-mile radius who has escaped such thefts; for many residents of central

California, confronting gang members casing their farms for scrap metal is a

weekly occurrence. I chased out two last August. One neighbor painted his pump

with the Oakland Raiders’ gray and black, hoping to win exemption from thieving

gangs. No luck. My mailbox looks armored because it is: after starting to lose

my mail once or twice each month, I picked a model advertised to resist an

AK-47 barrage.

I bicycle twice a

week on a 20-mile route through the countryside, where I see trash—everything

from refrigerators to dead kittens—dumped along the sides of less traveled

roads. The culprits are careless; their names, on utility-bill stubs and junk

mail, are easy to spot. This summer, I also saw a portable canteen unplug its

drainage outlet and speed off down the road, with a stream of cooking waste

leaking out onto the pavement. After all, it is far cheaper to park a canteen

along a country road, put up an awning over a few plastic chairs and tables,

and set up an unregulated, tax-free roadside eatery than to battle the array of

state regulations required to establish an in-town restaurant. Six such movable

canteens line the road a mile from my farm. For that matter, I can buy a new,

tax-free lawnmower, mattress, or shovel at the ad hoc emporia at dozens of

rural crossroads. Who knows where their inventory comes from?

Few

residence-zoning laws are enforced in the rural interior of highly regulated

California. My neighbors often plop down broken Winnebagos—three or four per

acre—and add a few Porta-Potties and propane grills, thereby creating a

hacienda of renters. You can earn the ire of a building inspector in Menlo Park

if your new fence is an inch too high, but out here in the outback, no one

cares if you crowd 40 adults onto your premises.

To be in a car

accident in rural central California, as I have been three times, is often to

have the assailant driver flee the scene, or to learn later that he lacked

license, registration, and insurance. About once every three years, I find a

car—again, lacking registration and insurance—that has veered off the road into

my vineyard, destroying thousands of dollars’ worth of vines, and been

abandoned.

Law enforcement

seems not so much overburdened as brilliantly entrepreneurial. Patrol cars

flood the highways as never before, looking for the tiniest revenue-raising

infraction; the police realize that going after the man who throws a freezer

into the local pond is costly and futile, while citing the cell-phone-using but

otherwise responsible driver is profitable. In 2009, the most recent year for which

traffic statistics have been released, the highway patrol issued 200,000 more

violations than in 2006.

As I write, my

local community is confronting a peculiar epidemic. Bronze dedicatory plaques

are being stolen from our ancestral institutions—churches, halls, clubs,

parks—many of which my grandparents and great-grandparents helped establish. No

records exist for most of the ancient dedicatory names, so all prior

benefaction has been erased from our collective memory—and all for the recycled

meltdown that supplies only a day or two’s drugs for the thieves. For central

California’s parasitic criminal class, melting down what the departed

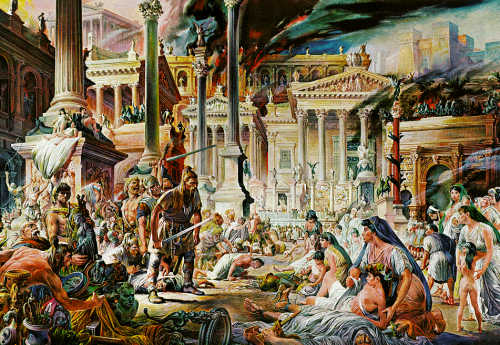

bequeathed us is a growth industry. It reminds me of the fifteenth-century

Turkish occupation of Greece, when scavengers pried the lead seals off the

building clamps of classical temples, destroying in decades what nature had not

damaged in centuries.

The world outside

my window reminds me a lot of what my grandfather told me about the wilderness

that his pioneer grandmother discovered on arriving here in the 1870s. We’ve

come full circle, tearing up what was handed down.

No comments:

Post a Comment