e21 Editorial

There is a sense among many commentators that the United States is

“becoming” more like Europe in that the government is growing beyond thresholds

that could be reasonably financed by the private sector. Putting aside the

merits of this view, the general description of the U.S. as “moving towards” Europe makes the distance left to be

traveled seem farther than it really is. The graphic below, constructed from

the International Monetary Fund (IMF) World Economic Outlook (WEO) data,

compares the combined government-to-GDP ratio of the 17 countries that use the

euro currency to the combined government-to-GDP ratio of the U.S.

Based solely on government outlays, the U.S. government is about 8

percentage points (or about 16%) smaller than that of the euro zone. However,

this is not really an apples-to-apples comparison because it does not include

the disparate accounting for health insurance premiums. In the euro zone,

health insurance premiums are generally financed directly through taxation; in

the U.S. employer-sponsored health insurance premiums are deducted from pay

checks or contributed directly by employers. The net effect is to leave

after-tax income lower to pay for health insurance.

Once accounting for the 5.6% of GDP (estimated from National Health Expenditures data) in employer-sponsored premium payments – but not out-of-pocket health expenditures or other private health care spending – total U.S. spending is nearly 47% of GDP. This is just 2 percentage points (or about 5%) less than for the euro zone. If one includes the $1 trillion annually in tax expenditures – government spending that counts as reduced revenue rather than government outlays – total government spending is already greater than in Europe. Even leaving aside tax expenditures, two percent of GDP is not a terribly big gap. Given the 20% increase in Federal spending since 2007, it is certainly not difficult to imagine an Obama Administration closing this gap (or exceeding it) by the middle of this decade.

Once accounting for the 5.6% of GDP (estimated from National Health Expenditures data) in employer-sponsored premium payments – but not out-of-pocket health expenditures or other private health care spending – total U.S. spending is nearly 47% of GDP. This is just 2 percentage points (or about 5%) less than for the euro zone. If one includes the $1 trillion annually in tax expenditures – government spending that counts as reduced revenue rather than government outlays – total government spending is already greater than in Europe. Even leaving aside tax expenditures, two percent of GDP is not a terribly big gap. Given the 20% increase in Federal spending since 2007, it is certainly not difficult to imagine an Obama Administration closing this gap (or exceeding it) by the middle of this decade.

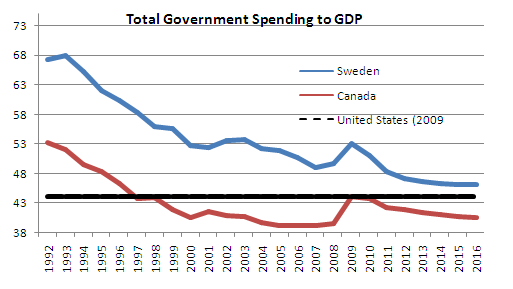

Total government spending in the U.S. is also roughly equivalent to

supposedly socialist economies like Sweden (Sweden is a member of the European

Union, but not the 17-nation euro zone) and traditionally statist economies

like Canada. The graph below compares total Swedish and Canadian government

outlays as a share of GDP to total U.S. government spending in 2009 (the last

year for which official data are available). If total U.S. spending remains at

2009 levels, by 2016 it will be 10% (or 4 percentage points) above Canada’s

spending. It is important to note that this total excludes health insurance

expenditures. Were employer-sponsored premiums included, total U.S. government

spending plus employer-sponsored health premiums would be about 11 percentage

points (25%) greater than Canada’s equivalent spending in 2016. Perhaps even

more surprising, government spending plus health insurance would put total U.S.

spending above Sweden’s projected 46% of GDP in 2016. Despite perceptions of

Sweden as a socialist society, the IMF projects that between 1993 and 2016, the

Swedes will have shrunk their government by 32% as a share of their economy.

Recent research finds that once adjusting for tax subsidies and tax

progressivity, U.S. government spending is comparable to Sweden in areas like total

social welfare expenditure.

IMF data on combined U.S. spending begins in 2001 so no direct comparison

with Sweden over the 1993-2016 period is possible. However, the IMF does report

that since 2001, total U.S. government spending has increased by 27% as a share

of the economy, with most of the increase occurring at the state and local

level. U.S. fiscal policy discussions focus mostly on the size of the federal

government since that is usually thought to be the only portion Congress

controls. But, that is not the case.

First, the U.S. facilitates state and local spending through the federal

tax deduction for state and local taxes and the interest paid on municipal

debt. With a 35% tax rate, the state and local tax deduction means state

residents pay only $0.65 for every $1 increase in state taxes. But the largest

federal contribution to state and local government has been federal transfers

that create moral hazard by ensuring state budgets that grow during good times

won’t have to be cut during bad times.

In 2003, the Senate demanded $20

billion in state and local aid as a condition of passing the tax cuts. This

sum was dwarfed by the $280 billion in state aid contained in the stimulus.

Part of the motivation for transferring funds to the states was to avoid the

fiscal contraction that arises due to state balanced budget mandates. But the

notion of a balanced budget at the state level is hugely misleading because so

much of state and local spending comes in the form of “off budget”

infrastructure spending. As of September 30, 2011 state and local governments

had more than $3 trillion in debt outstanding (L.105), which wouldn’t exist if budgets were always

balanced. As academic

research has made clear, the stimulus really just had the federal government pay for a portion of

state spending that would have otherwise been debt-financed. Much of the

so-called “Jobs Act” the President proposed also consisted of transfers to state and

local governments.

Beyond the size of government, the basic contours of U.S. policy debates

are the same as in Europe. The 2013 Budget that President Obama previewed in

the State of the Union Address is hardly different from the proposals of

Francois Hollande, the Socialist Party candidate for the French Presidency. The

President proposed large tax increases on high income

earners, a bank tax (in this latest iteration to finance mortgage debt

forgiveness), a minimum tax on corporations, and subsidies for favored

industries (manufacturing). Francois

Hollande proposestax increases on high income earners, a bank tax, an increase in the

minimum corporate income tax, and subsidies for favored industries. Hollande

also proposes “creating 60,000 teaching jobs,” which is very close, on a

population-adjusted basis, to President

Obama’s Jobs Act proposal. And to ensure no one loses sight of the essential similarities between

their platforms, Hollande explicitly referenced President Obama’s State of the

Union address when explaining the rationale for his tax increase:

Obama said he wants the secretary of a billionaire to not have to pay more than the billionaire [in taxes]. I want the same thing.

Much as “Europe” may appear to be a destination to which America is headed

on its current trajectory, the simple facts are that: (1) total U.S. spending

is already roughly equivalent to European spending on an apples-to-apples

basis; and (2) the European economic policy debate is largely the same as the

one occurring in America today. Rather than referring to an embrace of the

social welfare model, the notion of “moving towards Europe” may in a few years

mean reducing spending and balancing budgets. Sound familiar?

No comments:

Post a Comment