By PAUL GOTTFRIED

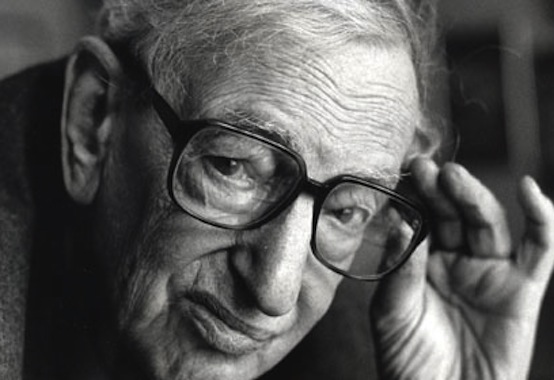

The death of Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm at the age of 95 two days

ago set me down memory lane. The one time I met this illustrious historian was

when Gene Genovese (who predeceased Hobsbawm

by just a few days) introduced him to me at a meeting of the American

Historical Association in Boston in 1969. I had just given a critical rejoinder

to a plea for a “humanistic Marx,” who had suffered from 19th-century German

anti-Semitism. In my response, I suggested that Marx himself had been

virulently anti-Semitic but that if one accepted his historical analysis his

personal prejudices should not seem important. After all, Marx was trying to

explain the course of human history and planning for a revolutionary future. He

was “not competing for the ADL liberal of the year award.” It seems Hobsbawm,

who was a dedicated member of the English Communist Party, agreed with my

sentiments and expressed concern about “the exotica being produced by

idiosyncratic, would-be Marxists.” Thereupon I took a liking to this dignified

gentleman in a three-piece suit, who had learned splendid English after growing

up in Vienna. He may have been a commie but he was clearly no bleeding-heart

leftist.

Moreover, I had

been reading on and off the first volume of what became his four-volume study

of the modern age since the French Revolution. This first volume, Age

of Revolution, 1789-1848 (1962),

was one of the best synthetic works on a tumultuous period in modern European

history, and unlike conventional, pro-liberal-democratic treatments of the same

sprawling subject, Hobsbawm made a strenuous attempt to integrate economic and

social change with evolving ideological fashions. Whatever his personal

politics, Age of Revolution and the succeeding volume Age

of Capital were

highly respectable scholarship. They came from a disciplined mind that operated

from a historical materialist perspective.

What is hard for

anyone who is not some kind of leftist ideologue to shove down the memory hole

is Hobsbawm’s lifelong dedication to communism, most particularly his

unswerving loyalty to Stalin’s memory. To his credit, Hobsbawm never hid his

loyalty to the Soviet experiment, and unlike his fellow Stalinist Eric Foner,

who scolded Gorbachev for dismantling the Soviet dictatorship, Hobsbawm never

grew into a fashionable, politically correct leftist. He died the communist he

became while living in Berlin in the early 1930s (or perhaps even earlier).

This shows an honesty and consistency that is admirable at some level but also

invites the deception and application of double standards that one expects from

the usual suspects. In what has become the authoritative obituary, the Guardian dwells on Hobsbawm’s impressive work as an

historian, his happy second marriage (after a failed first one and a child born

out of wedlock), and his decision to venture on to new Marxist research paths

in the 1970s. The paper also tells us that his friend and Marxist associate

Christopher Hill had dropped out of the CP by the 1970s but Hobsbawm chose a

different course. That path was of course one of total subservience to the

Soviet Union, although Hobsbawm had objected when Khrushchev in 1956 had dared

to comment on Stalin’s “cult of personality.”

One could only

imagine, as my son reminded me, what the same sources would say if Hobsbawm,

like Martin Heidegger, had once rashly come out in support of the Third Reich,

even if, as in the case of one of the West’s greatest philosophers, he had

subsequently withdrawn from politics. Obviously being a lifelong Stalinist is

not like being a temporary Nazi in 1933. It brings bouquets for one’s idealism

rather than a rash of anti-fascist tirades, masquerading as books, which are

reviewed in the elite press. But let’s not pick such an extreme example. Let’s

imagine that Hobsbawm went from being a Stalinist to something less ominous

than a fleeting Nazi enthusiast. What if he had gone from defending the gulags

to being an opponent of gay marriage? Would the Guardian have

treated him any worse when he died at 95 as a one-time “Marxist historian”? You bet it would.

No comments:

Post a Comment