It is time we re-examined the legacy of the late

Thumpa Sheil, the rabbit farmer and senator whose unfashionable views on

Apartheid, fearlessly expressed, made him the the shortest-serving minister in

Australia. Two days of notoriety in 1977 overshadowed Glenister Fermoy Sheil’s

other contributions to civic debate, which is a pity, because Thumpa was

nobody’s bunny. Over the course of his 13 years in Australia’s federal

parliament, he was a net contributor of common sense.

His

finest hour came when Gough Whitlam’s Labor government tabled the Racial

Discrimination Bill in 1975. Even as the conservative opposition was preparing

to bring down the government by vetoing the budget, it was too nervous to back

its instincts and block Australia’s first human-rights legislation.

It

was left to Thumpa, and a handful of other crazy-brave senators, to raise

questions about the bill’s questionable constitutional validity and its threat

to free expression. Only Thumpa and his backbench chums were prepared to defend

the reputation of the Australian people, impugned by the tabling of legislation

designed to cleanse society of ingrained racism.

‘The

passage of this bill would take some fundamental rights away from us, such as

the right of free speech, free discussion and publication’, Thumpa told

parliament during the bill’s second reading speech. ‘Far from eliminating

racial discrimination by making it illegal, the bill will highlight the

problems between the races and create an official race-relations industry with

a staff of dedicated anti-racists earning their living by making the most of

every complaint in much the same way as does the Race Relations Board in the

United Kingdom.’

‘This

bill’, Thumpa continued, ‘will create yet another large and expensive federal

government department. It will be headed by a race-relations commissioner with

the status of a High Court judge and with powers similar to those used in the

Spanish Inquisition.’

Thumpa’s

speech was dismissed as ‘Neanderthal grunts’ by Labor’s Jim McClelland, but

today his predictions appear to have been dispiritingly accurate. He was

getting ahead of himself with the line about the Spanish Inquisition, however;

that would require another legislative adventure in the form of the Racial

Vilification Act 1996. This was the legislation which newspaper columnist

Andrew Bolt was found to have broken in 2011 by suggesting that the rules for

claiming Aboriginal identity are not exactly black and white.

That

flawed and illiberal hate law bill, and numerous other audacious acts of

human-rights mission creep, went through virtually on the nod. Astute MPs on

both sides of parliament were aware of its illiberal implications, but only the

crazy brave like Thumpa are prepared to stand in the path of the human-rights

bandwagon in full and virtuous flight.

In

his novel On the Beach,

Neville Shute painted Australia as a good place to escape a nuclear war, but

the self-confident, level-headed people of this distant island continent have

been unable to avoid infection from the epidemic of virtue that took hold in

the 1970s, and gained strength as a tool with which to shame the Soviet bloc

into capitulation where conventional weapons had failed.

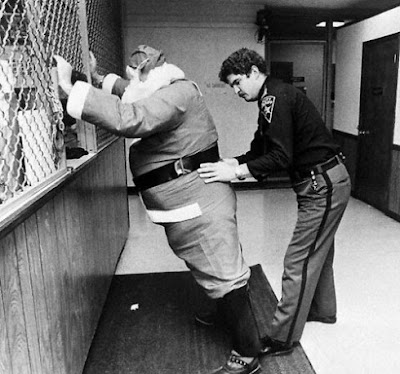

The

enforcement of human rights is now a multimillion-dollar, government-funded

industry in Australia, just as Thumpa said it would become. There are nine

official human rights bodies, one at a federal level and one for every state

and territory, each living off the public purse and pursuing petty claims of

discrimination against housing department officers, shopkeepers and nightclub

bouncers. Since Britain has more than enough problems of its own, I will spare

you the details of the department-store Santa in South Australia, who claimed

discrimination on the ground of a disability when the store manager asked him

to remove his glasses, or the Queensland public servant of Indian descent who

took umbrage when offered a cup of black tea.

It

seemed that until late last year, Australia as we know it would eventually

disappear under this rising tide of sanctimony. The federal government’s new

Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Bill, said to merely consolidate rights

but which in effect brazenly expands them, would sail through parliament on the

winds of worthiness, with attorney general Nicola Roxon at the bow as Celine

Dion sung ‘My Heart Will Go On’.

Quietly

at first, but with a swelling, indignant chorus, respectable Australians of

unimpeachable character began howling Roxon’s bill down. The contrivance of

describing race, gender, sexual orientation, disability or 14 other grounds for

victimhood as ‘protected attributes’ jarred; the inclusion of industrial history,

breastfeeding or pregnancy or social origin suggested overkill; the reversal on

the onus of proof, obliging alleged racists, misogynists and wheelchair kickers

to demonstrate their innocence, seemed a step too far. The ABC’s chairman, Jim

Spigelman, a lawyer of some standing, voiced his concerns about the outcome of

the Bolt case. ‘I am not aware of any international human-rights instrument or

national anti-discrimination statute in another liberal democracy that extends

to conduct which is merely offensive’, Mr Spigelman said. ‘We would be pretty

much on our own in declaring conduct which does no more than offend to be

unlawful. The freedom to offend is an integral component of freedom of speech.’

Ms

Roxon has now stepped down, not ostensibly over the bill, although the

unexpected controversy may have strengthened her desire to spend more time with

her family. It is unlikely to proceed: Australia’s prime minister Julia Gillard

has too many challenges in an election year to want to fight this battle. Incredibly,

the conservative opposition, which will almost certainly be in government in

seven months, is at last muscling up for a fight: the one it should have picked

in 1975 and again 20 years later.

In

January, when the recently appointed head of the Human Rights Commission,

Gillian Triggs, turned up to answer senators’ questions about the bill in

parliament, she might have expected an easy ride, just like her predecessors,

who frequently used such platforms to wag their fingers at the sorry creatures

of democracy who are forced to seek a popular mandate to find a voice in the

civic debate.

Shadow

attorney general George Brandis was well prepared, however, noting the right

the bill failed to address was the most important right of all in a democratic

society: the right to free speech. Political opinion would become a ‘protected

attribute’, although Professor Triggs was quick to add: ‘We would like to make

the point that not all political opinion is protected. The right is not

absolute; it is subject to certain constraints, most particularly along the

lines of broad principles of reasonableness and good faith.’

Senator

Brandis, who like Thumpa comes from Queensland, would not leave it at that.

‘Are you telling me that the judiciary or some other decision-maker will then

sit in judgement and say, “Your political opinion is not reasonable and

therefore it is not a protected attribute”?’

Professor

Triggs: ‘If the person putting the political view in a work context is doing so

in a way that amounts to some form of harassment of somebody in that workforce,

and the employer says, “You’re upsetting my employees; you’re doing this so

consistently and so insultingly that you’re disrupting the workplace, and I’m

going to sack you”, the question then might be: has this person been

discriminated against on the grounds of their political opinion?’

But

wait, the senator countered, I upset people every day in the course of my job

by expressing political opinions, ‘and rightly so, because that is what

pluralism and democracy mean’.

Ah,

said Professor Triggs, we are protecting the right to hold opinions; it was their inappropriate

expression that had the propensity to offend. If the expression of opinions

conflicted with another aim - public order, for example, or the maintenance of

a civilised workplace - then ‘in the end, decision makers will have to put

limits’.

Decision

makers, limits;

these are the kind of words that would have made Thumpa’s ears prick up, and

perhaps even those of his rabbits.

Senator

Brandis continued: ‘Suppose that in, say, a lunchroom in a workplace… there are

vigorously held and different views, some workers express an opinion among

themselves but in front of another worker, and the worker who hears the opinion

finds it extremely offensive and disturbing… Should the capacity to express

unwelcome political opinions - unwelcome to their auditor - be constrained?’

‘I

believe it can be, and ought to be, constrained, where the behaviour ultimately

becomes harassment - if you want to use that word’, replied the professor. ‘We

may get it wrong; the courts may get it wrong. But I think the critical point

is to accept that nobody is there objecting to the holding of the political

view; the objection is to the effect of that political view or the manner in

which it is delivered.’

Unlike

political opinion, attributes like age or gender or sexuality are objective

facts. They did not have to be demonstrated. As Senator Brandis pointed out:

‘There is no imperative for a 45-year-old man to go around saying, “I’m 45”.

That does not happen.’ Political opinion, however, means nothing unless it is

expressed.

Brandis:

‘I do not know if you are familiar with Czeslaw Milosz’s work The Captive Mind, or Arthur

Koestler’s book Darkness At

Noon… The whole point of political freedom is that there is an imperishable

conjunction between the right to hold the opinion and the right to express the

opinion. That is why political censorship is so evil - not because it prohibits

us holding an opinion but because it prohibits us articulating the opinion that

we hold.

‘We

all agree that there is no law in Australia that says you cannot have a

particular opinion. We all agree that there are certain laws in Australia,

including defamation laws, that limit the freedom of speech. My contention is

that there should not, in a free society, be laws that prohibit the expression

of an opinion… This attempt to say, “Holding an opinion is one thing but

expressing an opinion is quite different”, is terribly dangerous in a liberal

democratic politic.’

Thumpa,

for all his faults, would have got this point. Professor Triggs, evidently,

does not.

No comments:

Post a Comment