By Peter Coy

To most of the

world, the banking crisis that broke out in Cyprus in mid-March was as abrupt

and unexpected as an outbreak of Ebola. For Cypriots, it wasn’t sudden at all.

Many opportunities to steer the country in a better direction came along over

the years but were missed or never tried. Now the misbegotten decision by

European finance ministers to tax the accounts of ordinary depositors to help

pay for a bailout of the country’s biggest banks has become a source of

continentwide embarrassment.

The bailout mess

roiling the capital of Nicosia and the financial hub of Limassol has plenty of

only-in-Cyprus color: Russian oligarchs doing biznes in the

sunny Mediterranean, a simmering conflict with Turkey, a former president who

was educated in Soviet-era Moscow. Underneath the details, though, is a

frustratingly familiar pattern. A small country cleans up its act and joins the

international financial community. Money pours in from abroad. The cash is

spent or lent unwisely under the noses of inattentive or ineffectual

regulators. When losses mount, the money flows out as quickly as it came in. In

the end, it’s the little guys who lose the most.

Only five years

ago, Cyprus seemed to be in a sweet spot. The country had teetered on the edge

since a war in 1974 that left the northern third of the island under Turkish

control. For years it also had shaky government finances and a reputation as a

haven for foreign money launderers and tax evaders. But successive governments

worked hard to lose those bad habits as the price for admission to the European

club. Cyprus balanced its budget (for two years, anyway). And it tightened

banking regulations so successfully that today it’s in better compliance with

the 36-nation Financial Action Task Force’s rules on money laundering than

Germany, France, or the Netherlands.

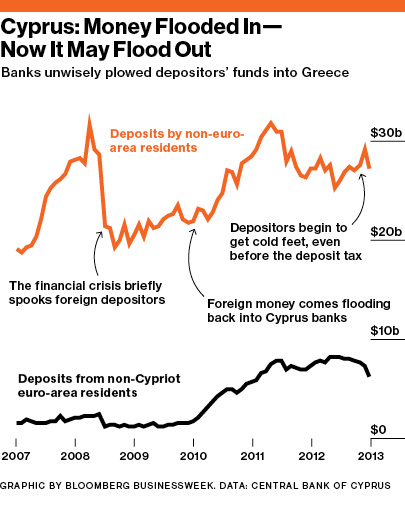

Cyprus was the

richest of the 10 countries that joined the European Union in 2004. Just four

years later it dropped its currency, the pound, in favor of the euro. There was

a brief episode of capital flight after the Lehman Brothers failure in 2008,

but it was soon reversed.

For a time,

being inside the EU and the euro zone benefited both Cyprus and foreigners

eager to invest there. It made the country—whose population of 800,000 or so is

no bigger than that of Jacksonville, Fla.—more attractive as a place to do

business. It particularly lured wealthy Russians, who appreciated the country’s

strong protection of property rights beyond Moscow’s reach and its 10 percent

corporate income tax rate (Europe’s lowest), not to mention the balmy weather

and a shared Orthodox faith. The storefronts of Limassol are plastered with

signs in Cyrillic. Roman Abramovich, the oligarch whose properties include

London’s Chelsea Football Club, operates Evraz (EVR), his steel, mining, and vanadium business, through a limited liability

company called Lanebrook in downtown Nicosia. There’s no evidence to support

German parliamentarians’ allegations that Cyprus is a haven for tax evaders. In

January even Russian tax authorities gave Cyprus a clean bill of health.

The

problem—again, a familiar one—was that Cyprus’s two biggest banks couldn’t

manage the flood of deposits. Cypriot regulators fell short as well. Athanasios

Orphanides, who worked for the U.S. Federal Reserve before becoming governor of

the Central Bank of Cyprus in 2007, realized the hot money could cause bubbles

and inflation in the domestic economy, so he limited the share that could be

lent domestically. Fine, except the big two—the Bank of Cyprus (BOC) and the Cyprus Popular Bank—simply shoveled the money westward into

loans in Greece. Greek government bonds were particularly attractive because

they offered higher yields at supposedly zero risk—since everyone knows

sovereigns don’t default, right?

A picaresque

character in the sorry tale is the wealthy Greek businessman Andreas

Vgenopoulos, a former national fencing champion who is nonexecutive chairman of Marfin Investment Group (MIG). He bought Cyprus Popular Bank in 2006, renamed it Marfin Popular Bank,

and led a rapid, risky expansion in Greece. It ended with the Cyprus government

forcing him out and seizing control, but not before his derring-do induced the

Bank of Cyprus to take similar risks to keep pace. Vgenopoulos’s bank lent

money to people who used proceeds of the loans to buy shares in his other

business, Marfin Investment Group. Vgenopoulos says there’s nothing wrong with

that. This January he sued Cyprus, asking it to give him back the bank and pay

damages.

Once Greece hit

the skids in 2010, it was inevitable that Cyprus would follow. Already by 2011

the government was effectively prevented from selling bonds by a junk credit

rating. It resorted to a €2.5 billion ($3.2 billion) loan from the Russian

government, due in 2016. The killer, though, was the pact reached in October

2011 to reduce the value of Greek government bonds by 70 percent. That produced

a loss to the Cyprus banks of more than €4 billion—the same in proportion to

the economy’s size as a $4 trillion loss in the U.S. President Demetris

Christofias, seemingly not realizing the severity of the blow, agreed to the

haircut without seeking offsetting aid for Cypriot banks. He eventually sought

a bailout, but, befitting a left-wing politician who earned a doctorate in

history in the Soviet Union, dragged his heels on cutting government spending

while inveighing against the “troika” of the European Union, the European

Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. Losses mounted.

Which brings us

to the current cock-up. Germany’s parliament insisted that creditors of the big

Cyprus banks share the pain of the bailout. The banks have few private

bondholders, so that left depositors. President Nicos Anastasiades, a

right-wing politician who succeeded Christofias in February, reluctantly agreed

to the tax on bank deposits in negotiations with the troika. But on March 19,

Cyprus’s parliament rejected the deposit tax by a 36-0 show of hands. Banks

remained closed as the crisis dragged on, and frightened Cypriots lined up at

cashless ATMs. One man was arrested for trying to bulldoze his way into a bank.

Cyprus-born

Christopher Pissarides, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2010, is only

slightly less incensed than the bulldozer man. In an e-mail exchange, the

London School of Economics professor said he was “appalled” by the troika’s

gambit. “Small countries be warned when joining the euro zone,” he wrote. “You

could be bullied anytime by your big brothers if it suits their political

objectives.” Bullying of Cyprus aside, the macroscale fear is that depositors

will expect the same thing to happen in Greece, Portugal, and so on. If they

yank their money out as a precaution, that could cause the failure of even

healthy banks.

In retrospect,

most or all of this could have been avoided if Cypriot banks had been prevented

from lending so heavily to Greece. Once it was clear that the Central Bank of

Cyprus was underregulating, the European Central Bank should have made noise,

even though at the time it lacked authority to dictate terms. When the halloumi hit the fan, the EU, ECB, and IMF should

have stood by Cyprus unconditionally. The time for tough love is before the

crisis, not during it.

Now it’s all

about keeping Cyprus from collapsing while appeasing creditor nations like

Germany. “This is not the end of the process but instead kicks off a further

round of negotiation with Moscow and Berlin,” Alexander White, a European

political analyst at JPMorgan Chase (JPM) in London, said in a note. That Europe’s leaders resorted to this

plan shows just how limited their options have become—which is why it’s so

important to avoid getting into jams like this in the first place.

When will we learn?

No comments:

Post a Comment