Banks

Battling to Survive

By

Pater Tenebrarum

Yesterday we had the opportunity to attend a presentation by the

treasurer of a European bank, which discussed the problems the European banking

sector faces since the beginning of the crisis era in 2008.

Many of these problems are obvious, but some of them are perhaps less

so. There are on the one hand the regulatory pressure to increase capital, a

plethora of new regulations and taxation that refers to the size of a bank's

balance sheet, regardless of its profitability. While such taxation only

amounts to about 20 basis points, it has to be seen in the context of currently

available margins in the banking business, which are dismal – once on does

that, the number actually strikes one as quite large.

Regarding the regulatory regime, European bank managers these days

apparently spend more time satisfying the demands of a whole horde of regulatory

bodies (a bank with a decent pan-European presence can count on having to deal

with up to 25 different regulators), all of which continually want to play

through stress test scenarios or are demanding data on this or that. Everything

has to be done to the perfect satisfaction of the bureaucrats concerned with

these oversight activities, down to the color of the paper the presentations

are printed on. The problem is of course that this is distracting managers from

what they should actually be doing, namely focus on the business.

Given the crisis situation, one should not be surprised at this sudden

avalanche of regulatory demands. However, as we have often pointed out

here, in a free banking system with 100% reserved sight deposits, all of

this would be completely unnecessary.

The most important problem faced by banks though are their funding costs

relative to the interest rates they can charge on loans.

Exploding

Funding Costs, Shrinking Interest Rate Margins

As a side effect of the crisis and the reaction of the ECB as well as

the Brussels based eurocracy to it, banks now have to deal with a funding

situation that is markedly different from what pertained prior to 2008.

One can infer the funding costs in terms of bond issuance via the

i-Traxx (ITRX) indexes on senior and subordinated unsecured bank debt. In

pre-crisis days the 5 year ITRX on senior unsecured financial debt traded below

50 basis points. Now, even after the ECB managed to calm the markets with its

'OMT' announcement, it stand at about 300 basis points.

The impact of the crisis on funding via customer deposits has been even

more remarkable. In 'normal times', a bank could count on having to pay less

interest on sight and savings deposits than was available in the money market

in terms of 3 month EURIBOR rates. Thus it was possible to simply lend on

deposits in the money market and thereby earn a small, but fairly 'safe'

interest margin. Since EURIBOR began to plunge in late 2008, the relationship

has reversed: since then customer deposit interest rates have remained

stubbornly above 3 month EURIBOR rates. There is no longer a relatively

risk-free spread that can be earned in money markets. On the other hand, banks

are loath to do without customer deposits, as they are regarded as a 'sticky'

funding source. As an example, a hedge fund may very quickly withdraw its funds

in a developing crisis situation. Most small depositors are far slower to react

and often don't react at all. Cyprus is in fact a good example for this, as

only a small percentage of depositors actually fled the Cypriot banks, in spite

of what were rather obvious warning signs. In addition, we can probably assume

that a certain portion of those who did withdraw their deposits from Cypriot

banks in time had insider information regarding the impending depositor

'haircut'. In short, even though customer deposits have become a headache in

terms of cost, they provide banks with an invaluable liquidity buffer in the

event of worsening crisis conditions.

One major reason why the cost of funding in terms of bond issuance has

shot up – a situation that is unlikely to reverse anytime soon – is in fact the

Cyprus affair. Even though euro area politicians continually stress the

'uniqueness' of the Cyprus 'bail-in', any halfway awake investor knows that

'bail-ins' are now indeed the new template for dealing with insolvent banks in

the euro area.

The Bundesbank brief to the German constitutional court, which we've discussed in a previous article, inter alia contains the Bundesbank's

opinion on ELA (emergency liquidity assistance) financing. On this point the

BuBa remarks that the ECB should be far more circumspect about granting

ELA and that insolvent institutions should simply be wound up. Bond investors

therefore are nowadays poring rather attentively over bank balance sheets in

order to calculate what precisely their risk in the event of a bank failure is.

Equity capital is the initial buffer, then comes subordinated debt and

senior bondholders are next in line. However, many European banks have issued a

great many so-called 'covered bonds'. The cover pools that stand behind these

covered bonds have to be deducted from the assets available for distribution to

bondholders: a great number of mortgage loans as well as sub-sovereign

securities that sit on bank balance sheets can actually not be touched by

these unsecured creditors if they back covered bonds. Thus a unique feature

that has contributed to the perceived safety of credit securitizations in

Europe has now ended up putting notable pressure on bank funding costs. Indeed,

these days the financing costs of financial intermediaries are a great deal

higher than those of non-financial corporates.

As a result of the foregoing, the traditional banking business of credit

intermediation – which according to the treasurer still makes up about two

thirds of bank earnings – is threatening to become non-viable. Net interest

rate margins have roughly been cut in half since 2008 and are now so small that

they offer very little margin for error. Banks will have to adapt to this

situation by attempting to grow other income sources, but there are clearly

noteworthy macro-economic consequences flowing from this.

Going

the Way of Japan?

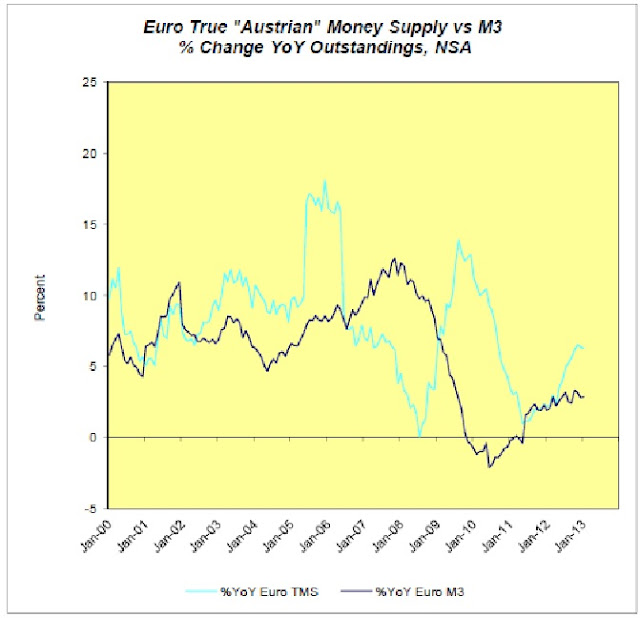

What follows from the above is that the era of willy-nilly credit

expansion by the commercial banking sector in Europe, which dominated the first

decade of the euro's existence, is over. This is also why the ECB has been

unable to create any notable money supply growth in the euro area, in spite of

occasionally increasing its balance sheet at an even faster pace than the Fed.

Regardless of how much central bank credit is made available – and even though

it provides temporary relief from funding stresses to some extent – it cannot

spark credit demand nor can it make banks more eager to expand credit on their

own given that they are faced with the need to keep much larger liquidity

buffers than before and are experiencing a collapse in their net interest

margins.

To be sure, the Fed is confronted with a very similar problem in the US,

but its modus operandi is different from that of the ECB, in

that it has created a great deal of deposit money directly with its 'QE'

operations. Every securities purchase from non-banks immediately increases not

only bank reserves, but creates deposit money in the system to the same extent.

Thus the broad US money measure TMS-2 (which excludes bank reserves) has grown

from roughly $5.3 trillion at the beginning of 2008 to $9.4 trillion at the

beginning of 2013. That is obviously an enormous inflation of the money supply,

which was accomplished in spite of the fact that US commercial banks have been

contracting credit up until about mid 2010.

By contrast, euro area TMS grew from €4 trillion at the beginning of

2008 to €5.1 trillion as of the beginning of 2013, a far smaller rate of

monetary expansion. It should also be pointed out that the great bulk of this

expansion occurred in the 'early days' of the post 2008 crisis phase, i.e.

between 2009-2010, before the euro area sovereign debt crisis went into

overdrive.

We strongly suspect that the increase in euro area money supply growth

that could be observed in 2012-2013 is mainly a reflection of the growth of the

carry trade in peripheral sovereign debt in this period – in other words, banks

in Spain, Italy, etc., created deposits in favor of their governments by buying

their bonds. This money has then entered the economy via government spending.

However, it should be obvious that this type of monetary expansion is highly

dependent on the state of play in the sovereign debt crisis and the continued

growth of public debt. Both are

in danger of receiving a significant damper.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the same basic conditions that pertained in post bubble

Japan nowadays appear to be a characteristic of the euro area. Bank credit

expansion is likely to stagnate or even go into reverse. This will continue to

put great pressure on all bubble activities in the euro area – many of the

capital malinvestments of the boom that haven't been liquidated yet are bound

to be liquidated as time goes on, and it will be very difficult to start fresh

bubble activities in spite of very low administered interest rates. As a

consequence, the growth rate of the supply of euros should begin to stagnate as

well. These developments should actually be welcomed, as one should certainly

not wish for a repetition of the boom-bust cycle that has laid Europe low.

Unfortunately, it all happens against the backdrop of vastly over-regulated and

over-taxed economies. If Europe were to implement a program of

far-reaching economic liberalization, cutting all the red tape, shrinking the

size of governments and lowering taxes, the foundations for a sound economic

recovery would now be in place. However, this is clearly hoping for too much.

No comments:

Post a Comment