by Peter C. Earle

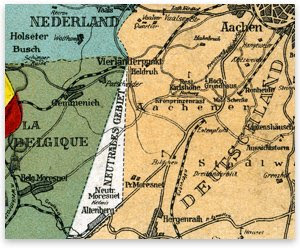

Can a community without a central government avoid

descending into chaos and rampant criminality? Can its economy grow and thrive

without the intervening regulatory hand of the state? Can its disputes be

settled without a monopoly on legal judgments? If the strange and little-known

case of the condominum of Moresnet — a

wedge of disputed territory in northwestern Europe, and arguably Europe's counterpart

to America's so-called Wild West — acts as our guide, we must conclude that

statelessness is not only possible but beneficial to progress, carrying

profound advantages over coercive bureaucracies.

The remarkable experiment that was Moresenet was an

indirect consequence of the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), which, like all wars,

empowered the governments of participating states at the expense of their

populations: nationalism grew more fervent; many nations suspended specie

payments indefinitely; and a new crop of destitute amputees appeared in streets

all across Europe.

In the Congress of Vienna, which concluded the war,

borders were redrawn according to the "balance-of-power" theory: no

state should be in a position to dominate others militarily. There were some

disagreements, one in particular between Prussia and the Netherlands regarding

the miniscule, mineral-rich map spot known as the "old mountain" —

Altenberg in German, Vieille Montagne in French — which held a large zinc mine

that profitably extricated tons of ore from the ground. With a major war

recently concluded, and the next nearest zinc source of any significance in

England, it behooved the two powers to jointly control the operation.

They settled on an accommodation; the mountain mine would

be a region of shared sovereignty. So from its inception in 1816, the zone

would fall under the aegis of several states: Prussia and the Netherlands

initially, and Belgium taking the place of the Netherlands after gaining its

independence in 1830. Designated "Neutral Moresnet," the small land

occupied a triangular spot between these three states, its area largely covered

by the quarry, some company buildings, a bank, schools, several stores, a

hospital, and the roughly 50 cottages housing 256 miners and support personnel.[1]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)